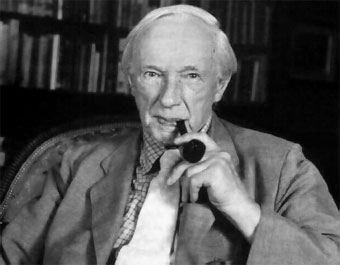

Der britische Philosoph George Edward Moore wollte in "proof of an external world" die Existenz einer Außenwelt bewiesen haben. Sein Argument ist unter dem Ausdruck "Hier ist eine Hand" bekannt geworden.

1. Das Argument von Skeptischen Hypothesen

Warum sollte überhaupt jemand bezweifeln, dass es eine Außenwelt, d.h. eine von der Erfahrung unabhängige Realität, gibt? Dafür gibt es eine Reihe von guten skeptischen Gründen (z.B. das Traumargument oder das Gehirn-im-Tank-Argument). Die meisten weisen diese Form auf:

(P1) Ich kann nicht ausschließen, dass H. D.h.: Ich weiß nicht, dass nicht‐

H.

(P2) Wenn ich weiß, dass w, dann weiß ich auch, dass nicht‐H.

Also: Ich weiß nicht, dass w.

Dabei sei H eine beliebige skeptische Hypothese und w eine beliebige Wahrnehmungsüberzeugung über die Außenwelt. In aussagenlogischer Form sieht das Ganze so aus:

(P1)

ØK(S,

ØH)

(P2) K(S, w)

®

K(S,

ØH)

Also:

ØK(S,

w)

Ich kann also nicht wissen, dass eine skeptische Hypothese nicht wahr und die Außenwelt vielleicht gar nicht real ist (Cartesianischer Skeptizismus).

2. Moores "Beweis" der Außenwelt

a. Schritt 1

Moores Gegenargument lässt sich wie folgt paraphrasieren:

· Hier ist eine Hand (hebt sich seine Hand vors Gesicht).

· Hier ist eine andere Hand (hebt sich seine andere Hand vors Gesicht).

· Es gibt also mindestens zwei außenweltliche Objekte.

· Also: Es gibt eine Außenwelt.

Wie aber kommt Moore auf derartige Behauptungen? Wir wollen uns Moores Gedankengang im Ganzen klarmachen. Zuerst fordert er uns auf, den Begriff "Außenwelt" richtig

zu verstehen. Wann

gehört etwas zur Außenwelt? Wenn es „im Raum antreffbar“ (to be met in space) oder, besser noch, „außerhalb unseres Geistes“ (external to our minds) ist.

Aber wie ist das wiederum zu verstehen? Eine Entität X ist außerhalb meines Geistes gdw. sich aus den folgenden beiden Behauptungen kein Widerspruch ergibt:

(B1) X existiert zu t.

(B2) Ich habe zu t keinerlei Empfindungen oder Wahrnehmungen (von t).

Außerhalb des Geistes (ein Teil der Außenwelt) zu sein heißt also, erfahrungsunabhängig – zu sein.

Laut Moore gehört es nun zur Bedeutung von Ausdrücken wie „Seifenblase“, „Blatt Papier“, „Hand“, „Socken“ etc., dass Dinge dieser Art erfahrungs‐ unabhängig sind. Er möchte also die Existenz der Außenwelt durch die Bedeutung von Wörtern beweisen:

„If I say of anything which I am perceiving, „That is a soap‐bubble”, I am, it seems to me, certainly implying that there would be no contradiction in asserting that it existed before I perceived it and that it will continue to exist, even if I cease to perceive it. (...) [A] thing which I perceive would not be a soap‐bubble unless its existence at any given time were logically independent of my perception of it at any time; (...) I think, therefore, that from any proposition of the form “There is a soap‐bubble!” there does really follow the proposition „There is an external object!” “There’s an object external to all our minds!”

- George Edward Moore: Proof of an External World, S. 164f.

Moores erstes Fazit lautet demnach: Um zu zeigen, dass die Außenwelt existiert, müssen wir zeigen, dass es Dinge außerhalb unseres Geistes gibt. Dazu müssen wir zeigen, dass es Dinge einer der Arten gibt, von denen gilt: Dinge dieser Art sind erfahrungsunabhängig. Und es ist eine analytische Wahrheit, dass z.B. Dinge der Art "Hand" erfahrungsunabhängig sind.

Aber ist das schon ein anti-(cartesianisch)-skeptische Einsicht? Nein. Dass bedeutet nämlich lediglich, dass gilt: Aus „Es gibt mindestens eine Hand“ folgt logisch

„Es gibt mindestens ein Ding außerhalb unseres Geistes“ Das wird der Cartesische Skeptiker problemlos zugestehen. Anders als z.B. Berkeley behauptet er ja nicht, dass Überzeugungen wie „Es gibt

Hände“ von mentalen Entitäten (ideas) und nicht von physischen Dingen handeln. Der Skeptiker behauptet lediglich, dass keine unserer Überzeugungen über die Außenwelt Wissen

darstellt.

Moores zweites Fazit lautet nun: Die Existenz der Außenwelt lässt sich im Prinzip auf beliebig viele verschiedene Weisen beweisen:

“[I]f I can prove that there exists now both a show and a sock, I shall have proved that there are

now “things outside of us”, etc; and similarly I shall have proved it, if I can prove that there exist now two sheets of paper, or two human hands, or two shoes, or two socks, etc. Obviously,

then, there are thousands of different things such that if, at any time, I can prove any one of them, I shall have proved the existence of things outside of us.”

- George

Edward Moore: Proof

of an External World, S. 165

Aber wie zeigt man an erster Stelle überhaupt, dass z.B. gilt: Es gibt mindestens eine Hand?

Schritt 2

“I can prove now, for instance, that two human hands exist. How? By holding up my two hands and

saying, as I make a certain gesture with the right hand, “Here is one hand”, and adding, as I make a certain gesture with the left, “and here is another”. And, if by doing this, I have proved

ipso facto the existence of external things, you will all see that I can also do it now in a number of other ways: there is no need to multiply examples. (...) [T]he proof which I gave was a was

a perfectly rigorous one; and it is perhaps impossible to give a better or more rigorous proof of anything whatsoever. Of course, it would not have been a proof unless three conditions were

satisfied (...), but all (...) three conditions were in fact satisfied by my proof.”

- George Edward Moore: Proof

of an External World, S. 166

[1]

“The premiss which I adduced in proof was quite certainly different from the conclusion (...).”(PEW, S. 166)

[2] “[I]t is quite certain that the conclusion did follow from the premiss. This is as certain as it is that if there is one hand here and another here now,

then it follows that there are two hands in existence now.”(PEW, S. 167)

[3] “I certainly did at the moment know that which I expressed by the combination of certain gestures with saying the words “There is one hand and here is

another”. I knew that there was one hand in the place indicated by combining a certain gesture with my first utterance of “here” and that there was another in the different place indicated by

combining a certain gesture with my second utterance of “here”. How absurd it would be to suggest that I did not know it, but only believed it, and that perhaps it was not the case! You might as

well suggest that I do not know that I am now standing up and talking – or perhaps after all I am not, and that it’s not quite certain that I am!”

(PEW, S. 166f)

Moores Argument lässt sich aber auch einfacher ausdrücken:

(M1) Ich weiß, dass es mindestens eine Hand gibt.

(M2) Wenn ich weiß, dass es mindestens eine Hand gibt, dann weiß ich auch, dass nicht in einer Dämon‐Welt lebe.

Also: Ich weiß, dass ich nicht in einer Dämon‐Welt lebe.

Bzw:

(M1) K(S,

w)

(M2) K(S, w) ® K(S, ØH)

Also: K(S, ØH)

(M1) stellt für Moore eine "Moore’sche Tatsache" dar: Eine Tatsache M ist eine Moore’sche Tatsache, wenn M sicherer ist als die Prämisse jedes Arguments dass zeigen könnte, dass nicht‐M. Moore behauptet also nicht, wirklich einen Beweis für die Behauptung „Hier ist eine Hand“ zu haben. Trotzdem dürften wir diese Behauptung als Tatsache hinnehmen, Da die Annahme (M1) weitaus sicherer (oder plausibler) zu sein scheint als jede skeptische Hypothese H, mit der man zeigen könnte, dass ich nicht weiß, dass es mindestens eine Hand gibt.

3. Was ist von Moores Beweis zu halten?

An Moores "Beweis" ist nur eines wirklich verblüffend: Dass ein so offensichtlich schlechtes Argument für so viel Wirbel gesorgt hat:

a. Moores ‚Beweis’ ist zirkulär: Moore setzt schlicht voraus (M1), was zu zeigen ist, dass es nämlich Dinge der Außenwelt gibt (die Conclusio).

b. Moore verweigert sich der Argumentation: Die Skeptiker geben ein Argument für die skeptische Konklusion. Moore beharrt schlicht darauf, dass das Argument falsch sein muss, gibt aber keine Gründe für diese Annahme an – abgesehen vom Insistieren darauf, er wisse, dass es mindestens eine Hand gibt.

c. Moores Strategie öffnet der dogmatischen Beliebigkeit Tür und Tor: Wann immer mir die Konklusion non‐p eines Argumentes nicht passt, kann ich mich auf den Standpunkt stellen, p sei eine "Moore’sche Tatsache". Das wirkt besonders plausibel, wenn p in meiner Gruppe als offenkundig wahr gilt.

Philoclopedia

Philoclopedia

Philoclopedia (Freitag, 15 Oktober 2021 03:29)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i7zt-tEYpoU&ab_channel=KaneB

Jacob W (Sonntag, 26 April 2020 13:43)

Anscheinend sind diese Zirkelschlüsse eine treibende Kraft in Moores Werk. Bei der Verteidigung des Common Sense ist es ja nicht anders: Die Wahrheit der Trivialitäten muss vorausgesetzt werden, damit sie gegen den Zweifel der Skeptiker verteidigt werden kann.